Malware Writeup: JS:Trojan:Cryxos.2550

While reviewing currently surging malware attacks back in January 2020, one in particular stood out: JS:Trojan:Cryxos.2550. Its appearances increased over 457% from the previous week. This isn’t a new malware by any means, as Trojan.Cryxos has been written about many times. However, this variant is rather new and since it’s surging, it is important to raise the question if you are protected. In short, if you’re a WatchGuard user then the answer is yes! Allow me to expand on the details of this threat though. About the Malware For starters, the family Trojan.Cryxos has been around for several years. It’s commonly associated with scareware or fake support call requests as described in F-Secure’s write up. You yourself may have previously received a pop-up of sorts that raised an alarm, inducing fear of “having been hacked” or “your computer alerted us that it is infected” or something else to that affect. If so, you may very well have been the victim of this attack in some fashion. Surely, it’s not the only variation that does this though. Moving past the general family, we first detected the particular variant I analyzed on January 23, 2020. It incorporates HTML, PHP, and JavaScript technologies. This isn’t entirely too uncommon for web pages, as these are fundamental languages, each used in their unique ways. HTML renders a web page’s frame, so to speak, and CSS is used to format its layout. JavaScript is used to dynamically render content on the client’s machine, whereas PHP is used on the backend server that’s not directly accessible to clients. The most interesting aspect of this malware is how JavaScript is used to render HTML content. For instance, there are eight “<script>” blocks that leverage JavaScript’s “document.write(unescape())” function – this function decodes an encoded string. Each block has a parameter passed into the function in the form of a URL-encoded string. Therefore, when that function unescapes the parameter’s content, it decodes into HTML content, which is then rendered as normal in the client’s browser. See Figure 1 for a visual representation.

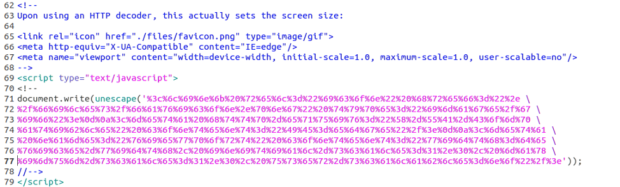

While reviewing currently surging malware attacks back in January 2020, one in particular stood out: JS:Trojan:Cryxos.2550. Its appearances increased over 457% from the previous week. This isn’t a new malware by any means, as Trojan.Cryxos has been written about many times. However, this variant is rather new and since it’s surging, it is important to raise the question if you are protected. In short, if you’re a WatchGuard user then the answer is yes! Allow me to expand on the details of this threat though. About the Malware For starters, the family Trojan.Cryxos has been around for several years. It’s commonly associated with scareware or fake support call requests as described in F-Secure’s write up. You yourself may have previously received a pop-up of sorts that raised an alarm, inducing fear of “having been hacked” or “your computer alerted us that it is infected” or something else to that affect. If so, you may very well have been the victim of this attack in some fashion. Surely, it’s not the only variation that does this though. Moving past the general family, we first detected the particular variant I analyzed on January 23, 2020. It incorporates HTML, PHP, and JavaScript technologies. This isn’t entirely too uncommon for web pages, as these are fundamental languages, each used in their unique ways. HTML renders a web page’s frame, so to speak, and CSS is used to format its layout. JavaScript is used to dynamically render content on the client’s machine, whereas PHP is used on the backend server that’s not directly accessible to clients. The most interesting aspect of this malware is how JavaScript is used to render HTML content. For instance, there are eight “<script>” blocks that leverage JavaScript’s “document.write(unescape())” function – this function decodes an encoded string. Each block has a parameter passed into the function in the form of a URL-encoded string. Therefore, when that function unescapes the parameter’s content, it decodes into HTML content, which is then rendered as normal in the client’s browser. See Figure 1 for a visual representation.

Figure 1: The Pink Encoded String Decodes into the Blue Text

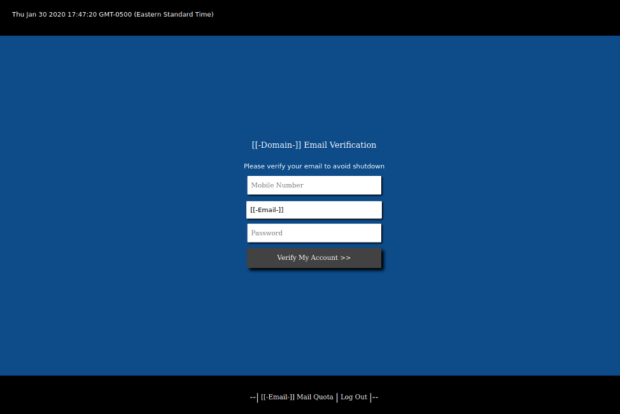

The pink text on lines 71 through 77 is the URL-encoded version of the blue text between lines 65 and 67. After reversing the encoded strings, they are all HTML content using inline CSS for styling. Where the concern in particular arises with this variant is the action to take once the web page’s form is filled out and submitted. As with many web pages, for example a user login screen, users must fill in the data and submit it for authentication. This is done using HTML’s POST method. The POST method sends data to a server to perform some action, which would typically be to verify said user does indeed have a user account with the web application and allow access if so. That said, the POST method in this case is sending the data collected to an attacker-controlled server at the domain “hxxps[:]//dotcodesoultions[.]com/bb/result[.]php”. Here we have a prime example of a phished login page. Looking at Figure 2, you can see that the page is requesting a mobile number and password.

Figure 2: Final Rendered Web Page

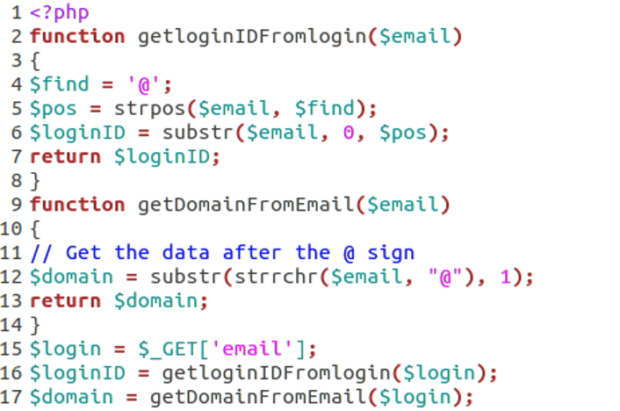

More About Encodings UTF-8 is a common encoding format to accommodate the many languages on this earth. HTML5 converts input into UTF-8 by default. I won’t go into too much detail about it but if you are curious, refer to this W3Schools link. What I will do is provide a good example to help you understand what this means. Say we have the string “Hello, from WatchGuard!” that we want to URL encode, minus the double quotes on either side. If we enter this string into an online URL encoder, we get the following HTML URL encoded result: “Hello%2C%20from%20WatchGuard!”. This is simple to read. There are recognizable text characters making up words, which in turn are separated by “%20”. The “%20” is the UTF-8 encoded version of a space represented in hexadecimal value; “%2C” is a comma. Since HTML URL parameters cannot include spaces, the spaces are represented using this encoded schema. To further obfuscate the contents of this string, we can first encode using UTF-8 and then URL encode that result. Here’s an example of that using the same “Hello, from WatchGuard!”: “%48%65%6C%6C%6F%2C%20%66%72%6F%6D%20%57%61%74%63%68%47%75%61%72%64%21”. You can see that this isn’t nearly as recognizable, though you can reverse it using online tools. Each sequence of “%XX” is the UTF-8 hexadecimal representation of a single character; “%48” is “H,” “%65” is “e,” etc. Summary and Conclusion In summary, I suspect this threat is triggered when a user clicks on a link within an email message. The email address is passed as a parameter to this web page and extracted using PHP’s “$_GET[‘email’]” function which pulls the parameter assigned to the “[‘email’]” field. As the page is loading, the email is analyzed, username (whatever is before the “@” character) and domain (whatever is after “@”) are extracted, and available for reference. Figure 3 shows how this is done.

Figure 3: PHP Functions to Extract "$loginID" and "$domain" from “$login”

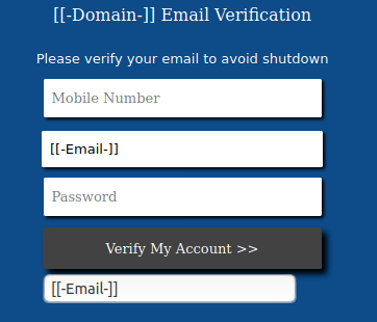

Line two starts the function “getLoginIDFromlogin” with “$email” passed as a parameter. On line seven, the “$loginID” is returned – the value of which is the first character of “$email” up to, but not including, the “@” symbol. Line nine starts the “getDomainFromEmail” function with “$email” passed in as the parameter as well. The “$domain” returned on line 13 consists of the content in "$email" starting at the position of, but not including, "@" until the end of "$email". What’s not clear is why there is random text that just seems off, such as “[[-Domain-]]” on top of the form or “[[-Email-]]” in the second form box. I suspect this data should be updated to reflect the captured username and domain names. For instance, when the domain is extracted from the corresponding email address, the form header would read something like “<COMPANY DOMAIN> Email Verification” and the second form box would auto-populate with the user’s email address. One last note to mention is a hidden box below the “Verify My Account >>” button but it doesn’t seem to add any value. See Figure 4 for reference.

Figure 4: Close Up of HTML Form Fields